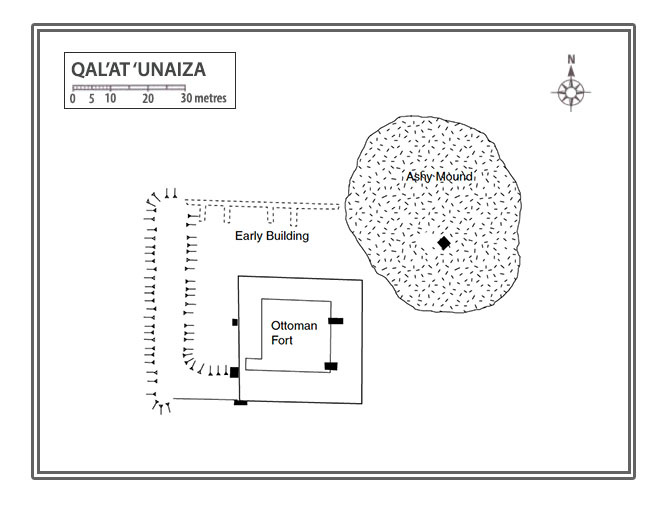

Qal’at ‘Unaiza stands on the central Jordan plateau, next to the Desert Highway and 400 m to the east is Mahattat ‘Unaiza, one of the stations on the Hijaz railway. The nearest modern settlement is the village of Hashimiyya, located approximately 3 km to the north. The landscape of this area is dominated by Jabal ‘Unaiza, an extinct volcano, located 2 km to the west of the fort, which has covered the surrounding area in a thin layer of basalt. The site comprises the Ottoman fort and several associated walls belonging to an earlier building. There is also a large depression to the north of the fort, which may originally have been a reservoir.

The Ottoman fort is a square building (28 m × 28 m) built of black basalt with white creamy limestone used for the quoins (these have mostly been robbed out and replaced with other stones in the restoration carried out in 2003) and standing to a maximum height of 8 m. This is the largest of the Ottoman forts in Jordan and several features indicate that the design of the fort was adapted to a pre-existing structure.

The east side of the Qal’at ‘Unaiza, facing the desert highway, contains the gateway, located north of the centre. Much of the south wall was rebuilt in October 2001 on new foundations, which project 0.5 m. from the exterior face of the wall. As recently as 1986 the south wall was mostly complete, with three stepped crenelations visible at the top and a small machicolation projecting from the wall at the first-floor level. The west side of the fort overlies and incorporates part of an earlier building. Besides the traces of an earlier building, this wall contains few features of any interest, except two small, square openings visible at the first-floor level. The north wall also stands to its full original height in several places, with the remains of, at least, two stepped crenelations still visible.

The interior comprises a large central courtyard, with vaulted rooms built around each side. The entrance is located at the east wall and comprises a large barrel passageway leading directly into the courtyard.

The vault is coated with plaster and decorated with a simple motif comprising a band of interlaced semicircles, below a band of triangles.

The courtyard is larger than at the other Hajj forts and was paved with basalt cobbles, set in lime mortar. Approximately in the centre of the courtyard, there is a vaulted subterranean cistern with a single manhole in the roof. The cistern is fed by a drain/channel running from the southwest corner of the courtyard.

The north range comprises a group of five small, vaulted rooms. Unfortunately, the original courtyard facade on the north side has been replaced by a more recent wall, of less skilful construction. However, clearance work carried out in October 2001 exposed the original line of the Ottoman wall, with the positions of the doorways. The south range comprises four rooms, each of near-identical design, comprising a rectangular area, roofed with a barrel vault, with two small openings set into the rear wall. The east range comprises three rooms, in addition to the vaulted entrance passage described above. The only other features of the east range are two staircases, on either side of the entrance vault. Both staircases have deteriorated badly, and it is not clear whether they would have been open or covered with vaults.

It is clear from historical accounts that the Ottoman fort stood next to a rain-fed cistern (or cisterns) which would have supplied the needs of the Hajj caravan. By analogy with other forts the reservoir(s) would have been located within 50 m of the fort, however, no definitive location was identified at ‘Unaizah. The most likely location for the cistern is a rectangular depression, aligned east-west, immediately to the north of the remains of the early building. The depression is not natural due to the absence of basalt boulders, which elsewhere, cover the landscape. Further support for this theory is provided by the existence of a wide channel, which leads to the depression on the west side. It is possible that the stone lining of the cistern was robbed to provide building stone for the nearby station.

It seems likely that there was a Roman presence at the site, as early as the 2nd century, in the form of a caravanserai that may have been associated with the Via Militaris. This early building was almost certainly connected to the nearby fort at Da‘ajaniyya. There is, however, no evidence of any later occupation at the site until the 16th century.

In 1563 Mustapha Pasha lists the site of Khan ‘Unaiza between Hasa and Ma‘an. It is not clear whether this is the Ottoman fort which still stands or the remains of the Roman caravanserai which may have been re-used in the first years of Ottoman rule. However, Barbir, following Mehmed Edib, suggests that the fort was built in, or soon after, 1576, by Sulayman Pasha who was also responsible for the construction of a fort at Hadiya.

In 1709, Murtarda ibn ‘Alawan arrived at ‘Unaiza, carrying water from Hasa because of the heat of the sun. He describes ‘Unaiza as a spacious building, larger than expected, well maintained and not in a ruinous condition. He states that it was owned by the Bani ‘Idha to impress people with their power.

In the early 19th century ‘Unaiza was inspected by engineers working for Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha. They describe the fort as a large square building standing next to a cistern of the same size. The interior of the fort, including the gateway and rooms, was described as being in a ruinous condition and this, combined with the fact that it was only half a day’s journey to Ma‘an, led the inspectors to assert that this stop was not used by pilgrims.

In 1896, Gray Hill visited the fort on his way to Petra after hearing a report that there was water in the cistern. Whilst there he enjoyed, ‘the warmth of a great bonfire of scrub gathered by our men’ and the view of a fine black mountain (Jabal ‘Unaiza). The following year, on 19th March 1897, the German scholars Brünnow and von Domaszewski followed the Hajj route north from Ma‘an and reached ‘Unaiza after a journey of 5 hours and 53 minutes. To the east of the Hajj route, they noted a walled cistern filled with water, which may be identical to the cistern within the compound of the railway station.

In the early 1900s, a railway station was established to the east of the Ottoman fort. In 1916 it became the terminus of a 36 km branch line leading to Shobek, from where wood was collected to fuel the engines of the Hijaz railway.

In 1972 the Jordanian Antiquities Department registered ‘Unaiza as an Antiquities Site and made a basic survey of the fort. In the late 1990s, the fort was included in the Dana Archaeological Survey, which identified the pre-Ottoman building at the site as ‘another large classical site on an ancient road that leads to the Ma‘an oasis’.